It’s 1980-something, and Neil Young just shouted “CDs are soulless” at the inaugural meeting of MAD, Musicians Against Digital. Maybe he didn’t shout it, but he definitely said it around that time, that group really did exist and Neil was a member.

But here’s the thing, he wasn’t alone in feeling this way about a disruptive new technology.

Major labels, record stores and producers all expected CDs to cause them real hardship. For labels, this pain would be most acutely felt in production facilities that would have to convert manufacturing processes. Record stores, at that time, had promotional boxes designed for 12 inch LPs, not 4.7 inch CDs. Redesigning shelves and floor plans was no one’s idea of a good time. And producers were wary that the previously inaudible white noise of the studio would now be crystal clear on digital reproductions. Anxiety ensued.

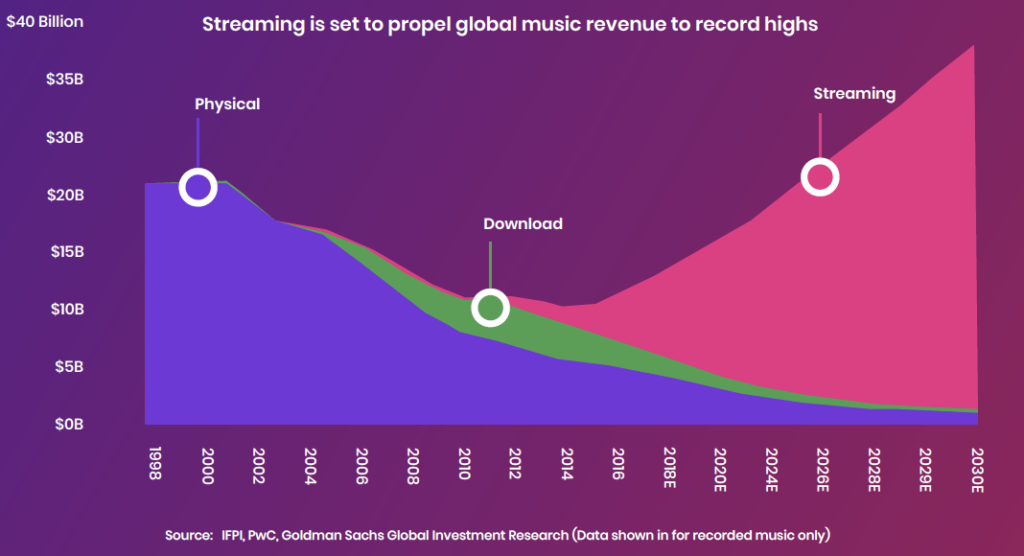

You may be familiar with what happened next. Historic, industry changing revenues, in the tens of billions of dollars annually, for about two decades. Fast forward to 1999 and those soulless plastic discs delivered the record high industry revenues illustrated on the chart below.

Maybe you weren’t familiar with that first music tech anecdote and the industry’s reluctant adoption of CDs. But I suspect you know what happened starting in 1999. Napster. Piracy. Illegal File Sharing. An industry in a painful, decade-long economic backslide.

Then, in about 2013, the chart begins to climb back up and to the right, propelled by legal digital downloads and streaming. As it was with Neil Young, MAD and the CD in the 1980s, the rise of streaming wasn’t met with arms wide open. Thom Yorke, the colorful Radiohead frontman, referred to Spotify as “the last desperate fart of a dying corpse” – CDs are soulless, redux.

It’s been said that technology upends the music industry about once every decade. Faster-playing 78s gave way to long playing (LP) albums and 45s in the 1950s and 1960s; cassettes and eight-track tapes proliferated in the 1970s. Streaming is the latest means of distribution in a laundry list of innovations that has caused mild heart palpitations amongst those in the industry, before being widely embraced.

As the distribution model changes with each dynamic new technological advance, so too do the incentives to game the system.

Alan Krueger distilled the economics of streaming and the incentives to misbehave in his 2019 industry tour de force, Rockonomics, explaining:

“[Royalty] payments are apportioned to song rights holders according to their share of streams on the service.

A hypothetical DSP has 100 billion songs streamed in a year, collects $600M in revenue from paying subscribers, and pays two-thirds of its revenue ($400M) to rights holders. A hit song accounts for 100 million streams on this service (which equals .1% of total streams), the payout to the rights holder of that song will be 0.1% X $400M = $400K.

This calculation assumes a lot of good faith.

Some streaming services have been accused of inflating streams for favored artists, or those with an equity stake in the company. Questions linger about how revenues are computed and whether revenues are shifted to other aspects of the business to avoid being subject to royalties.”**

Even on good faith, communicating billions of lines of data across countless disparate systems to tens of thousands of participants has undeniable potential to create a leaky bucket. And when that bucket is overflowing with streaming royalties – set to exceed $30B by 2030 – it’s best to trust, but verify, as the old proverb goes. Audit rights exist for a reason.

And that’s why we built Beatdapp. Mic drop.

*Alan B. Krueger, Rockonomics, P. 178

**Alan B. Krueger, Rockonomics, P. 181