Streaming fraud is a multi-million dollar problem in our industry. Don’t just take our word for it: Rolling Stone, Music Business Worldwide, Billboard, Variety, Quartz and too many others to name have been on this beat for some time.

Tim Ingham, Publisher of MusicBusiness Worldwide, sums up the incentives driving fraud like this:

- Streaming fraud is quite a simple beast to comprehend, because it always serves one of two, non-mutually exclusive purposes:

- (i) Deliberately inflating metrics which affect an artist’s perceived popularity – upping their chances of getting signed, or their chart success etc.;

- (ii) Inflating the revenue share that an artist (and/or their fellow rights-holders) receives from streaming services.

From these sources and our own discussions with leading experts from all corners of the industry including: labels, DSPs, distributors, artists, managers, and even a couple of streaming bot farm operators, the fraudulent streaming activity range typically nets out at 3-10% of all annual streaming activity.

This leads to questions like:

what does 3-10% represent in lost revenues? Is that a lot? Should we care? And if so, is there a solution to fix this?

Let’s zoom in on the North American market. In 2019, North America recorded ~1.15 trillion streams. Now, recall that 3-10% of streaming activity is estimated to be fraudulent. Taking the lower-end of that range, let’s say 5%, and the 2019 North American streaming figures, we could estimate that ~57.5 billion streams were fraudulent. At the top end of the range, we’re talking about ~115 billion fake streams.

Let’s ask Drake (you know, from Degrassi) to help us put these numbers into perspective. In North America, Drake has been Spotify’s most streamed artist of the last decade. Over that period, publicly available figures show that he’s accumulated an eye-popping 50 billion streams.

This means that our 2019 North American estimate of ~57.5 billion fraudulent streams are ~7.5 billion more than Drake has earned over the past decade.

In dollar terms, Drake’s decade of streaming is valued at north of (no Canada pun intended) ~$220M USD by applying the approximate, albeit, imperfect Spotify blended per stream rate of $0.0044 per play.

Applying the same formula to the low end of the fraud range, illicit activity is driving $253M USD to those deliberately inflating their metrics, driving fraudulent revenue, or both. Since advertising and subscription revenues are divided pro-rata based on market share, every illegitimate stream is costing every legitimate artist and label by diminishing their slice of the pie.

Now, run the same numbers but using the estimates at the top end of the fraudulent activity range, and an approximation of streaming volumes for the whole world. Your inputs become 10% of streams (vs. 3%), 2.3 trillion (2x North America) total streams, and $0.0044 per stream:

10% * 2.3 trillion streams * $.0044 per play = $1,012,000,000…

There is an obvious reason to disagree with this global analysis: because some emerging markets have yet to monetize streaming via paid subscriptions, as we have in North America, the per stream rate estimate is high, and at least the economic incentive for fraud is diminished (perception fraud, that is inflating one’s position on the charts, remains).

That may be true today, but this isn’t the type of problem that, if left unchecked, improves as the industry becomes more profitable. Just ask anyone who works in digital advertising. As I have written before, if the industry is going to meet or exceed its revenue projections for the balance of the decade, emerging markets will have to monetize their streamers. This increases both the value of each stream, and the incentives to commit fraud.

This brings us to whac-a-mole, the most commonly used analogy to describe fraud in the industry, and what we should do to combat it.

If you haven’t played whac-a-mole recently, a refresher:

- In the game (pictured right), you’re a frenetic, mallet wielding, Conservation Officersmashing every mole that dares show its smug mole-y face through the hole in the board.

- The mole is an infuriating, persistent and regenerative tormentor that keeps coming back no matter how effectively you – and you alone – swing that mallet.

- Eventually, you get frustrated. F%&* moles, you think!

- Since you are a sentient being capable of strategy and reasoning, you invite a few friends over to join the game.

- Each of you stands over the board, covering a hole or two, and together, you beat the moles at their own game.

Right now, as an industry, we’re playing hundreds of individual games of whac-a-mole to fight fraud. We’re developing unique internal systems and solutions to analyze patterns and detect inconsistencies, but as we’re learning, so are the moles. It’s hard to keep pace when you’re fighting alone; the moles are winning, to the tune of $150M-$$1.01B per year.

F&^%ing moles!

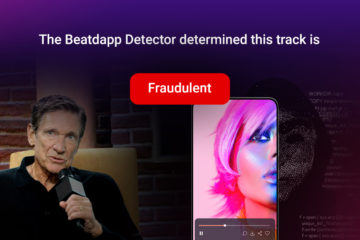

Beatdapp has a solution for that. And without giving away all the goods in this blog post, you can think about it like this:

We anticipate that the biggest limiting factor in working together is a universally held and legitimate concern about sharing sensitive information with competitors. We get that, and have a solve for it.

So if you’re interested in fraud detection, reach out and message me, we’re already building with you in mind. The tech might be complex, but the solution is as simple as the last time you beat whac-a-mole.